Space race gets additive advantage

The UK government aims to capture 10% of the global space industry by 2030. Kieron Salter, CEO at the Digital Manufacturing Centre and Mike Curtis-Rouse, head of manufacturing for space at the Satellite Applications Catapult look at whether additive manufacturing can unlock this ambition.

The UK is experiencing something of a space boom, with the industry trebling since 2000. Government reports suggest that the sector currently generates around £15 billion per year and supports more than 40,000 jobs across 950 different organisations in all 13 regions of the country. But far beyond its commercial appeal, developing a local space industry is critical to maintaining the nation’s security interests and telecommunication capabilities.

“The UK is well-positioned to take a leading role in the international space industry,” begins Keiron Salter, CEO at the Digital Manufacturing Centre. “We have vast engineering and scientific capabilities and a long history of British innovation at the frontier of humanity’s greatest challenges. Technology transfer from our world-leading motorsport and aerospace industries as well as our problem-solving capabilities have set us up for space success. In the past decade, we have really seen the UK space sector gain traction and now, with high-profile private space enterprise and the conclusion of Brexit, this drive is only set to increase. That is not to say it will be easy, but our collective ambition has already shown progress.”

Growth is being accelerated by government investment through the Satellite Launch Programme and other initiatives, which aim to establish commercial vertical and horizontal small satellite launches from UK spaceports by 2022. This entails funding for numerous projects, including £99 million for a new National Satellite Test Facility in Harwell and £31.5m to help kickstart the provision of vertical launch services from Scotland. There is also the potential creation of seven new spaceports, around the UK, from Sutherland to Cornwall, Shetland to Snowdonia.

If the substantial funding was not a clear enough sign of intent, the creation of a regulatory framework surely is – the Space Industry Act 2018 – which informed the creation of the Space Industry Regulations 2021, Spaceflight Activities (Investigation of Spaceflight Accidents) Regulations 2021 and Space Industry (Appeals) Regulations 2021. These cover everything from launch and return (space and sub-orbital), to procurement of UK launch technologies, operation of satellites, operation of spaceports and the provision of range control services.

Central to the UK’s space aspirations is the Satellite Applications Catapult (SAC) – an organisation at the heart of the satellite services revolution. With facilities across the UK and co-located with the Buckinghamshire LEP and Oxford-Cambridge ARC, it has been created to drive the adoption of space technology as well as shape and sustain the ‘world of tomorrow’, the Catapult is one of nine such entities created to transform UK capability in key areas. SAC engages with industry, helping organisations make use of, and benefit from, space technologies, and brings together multi-disciplinary teams to generate ideas and solutions.

“The fundamental purpose of the Satellite Applications Catapult is to ensure that the UK is a world leader in space technology and its applications for industry and society,” explains Mike Curtis-Rouse, head of manufacturing for space at the Satellite Applications Catapult. “We help to bring new technologies and services to market, connecting industry with academia to get new research off the ground – literally – and accelerate time-to-market. We are making a concerted effort to address the industry’s most significant challenges, streamlining manufacturing and reducing launch costs by turning to state-of-the-art processes and materials pulled from other existing and mature markets.”

Additive cuts the weight

While established manufacturing practices and materials have been thoroughly exploited to their maximum potential, the space sector’s attention and hope have focused on new, exciting and innovative materials and production processes. This is particularly relevant to the UK, which can capitalise on its burgeoning space industry’s agility to embrace new technology, like additive manufacturing (AM).

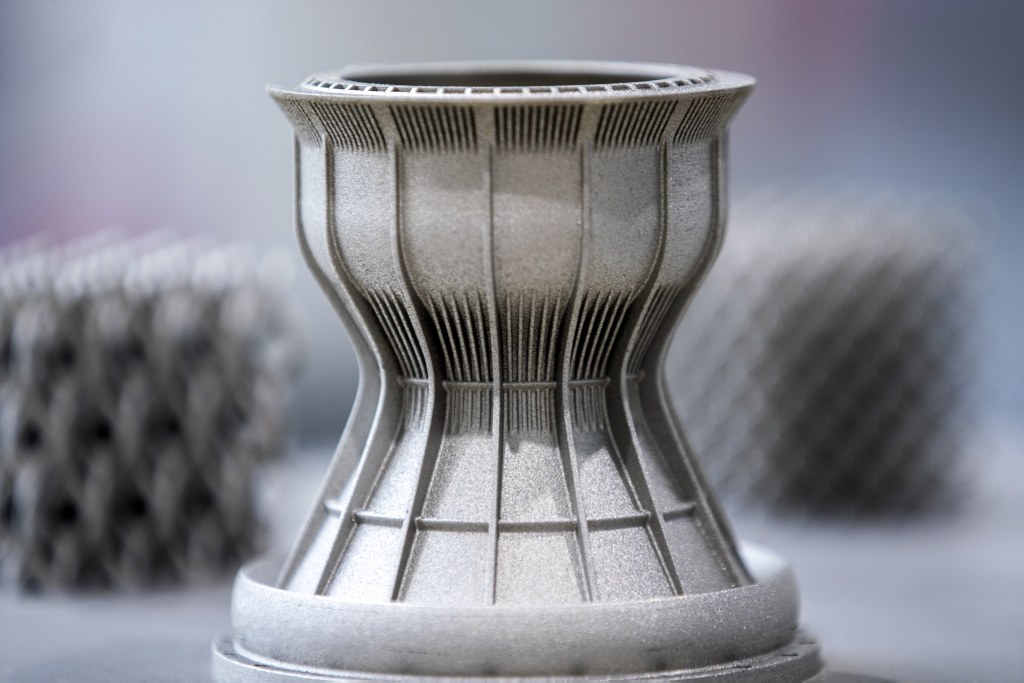

Both Salter and Curtis-Rouse highlight the rapid advancement of AM and advanced composites over the past decade. Each technology is now reaching maturation, in terms of both commercially viability and capacity for volume production. In many ways, AM is well-suited to the requirements of the space industry. Economical production runs can be as low as one unit, parts can be made on-demand, lead times are virtually non-existent and – perhaps most importantly – AM can be used to make parts that are not feasible via any other means.

“Additive manufacturing is opening up unprecedented possibilities in the space industry,” explains Curtis-Rouse. “When it comes to material efficiency, part design and lightweighting, AM is entirely unique. We can make hollow parts with material placed only where necessary, algorithm-optimised to provide the required performance with absolutely minimal weight. It may be a few grams at a time, but when you multiply it across all components, across both the payload and launch vehicles, the potential weight savings could provide a step-change in overall capability and importantly, reliability.”

One only has to look at NASA’s embrace of additive manufacturing to realise that it is a solution to many of the space industry’s most significant challenges. The difficulty of properly provisioning the International Space Station (ISS) with spare parts, for example, requires 13.2 tonnes of parts in orbit, 3.2 tonnes of restocking each year and 17.7 tonnes of spares sitting back on earth, ready to fly. What if some or all of them could be made on the station itself? Of course, the raw materials would still need to be delivered, but it would hugely simplify that small, highly complex and incredibly expensive supply chain.

For its future Artemis moon missions and the eventual trip to Mars, NASA is investigating the possibility of AM using moon dust. It is testing the concept in the microgravity environment of the ISS, using moon regolith – or rather, a human-made replica – to create fixtures and fittings. Given the scalability of the technology, it is entirely possible that AM could be used to manufacture lunar habitats and, equally, Martian bases when the time comes.

If AM’s future in the space industry is clear, what are we doing here in the UK? Well, a Midlands-based business has identified the opportunity and is eager to lead the charge. Already working alongside SAC and members of the Westcott Space Cluster and Harwell Space Cluster, the Digital Manufacturing Centre (DMC) is a newly-launched facility that is enabling the UK’s most advanced sectors through engineering-led AM production. Built upon well-established UK engineering knowledge and leadership, the DMC embraces Industry 4.0 principles with extensive connectivity and is actively collaborating with AM industry leaders, like Renishaw.

“The key differentiator between the DMC and the UK’s existing additive supply chain is that we are far more focussed on the application and work collaboratively with our customers to solve their problems,” says Salter. “We explore material selection, understand and appreciate the in-service requirements and have significant experience and expertise in the production side. This puts us in a unique position to work with the space sector.

“With a new ‘clean sheet’ capability and backed by an existing high-performance advanced engineering business, we are taking a different approach to space. If the UK is to compete internationally, the ‘old school’ space sector needs to become far more agile in development. At the DMC, our vision and engineering leadership is allowing us to take advantage of – and harness – disruptive processes and technologies to meet the new and evolving requirements of the modern space sector.”

The home advantage

While the UK’s advanced engineering and manufacturing industry is growing, the supply chain could still be considered limited and immature – particularly when it comes to AM. There is, perhaps, no better illustration of the supply chain’s shortcomings than British industry titans like BAE and Rolls-Royce investing in, and researching, in-house additive capacity. If the space sector is set to grow as anticipated, it will undoubtedly require huge advanced manufacturing capacity – particularly if it is to reach its 10% target.

“What little AM capacity exists within the national supply chain is almost entirely tied up in so-called ‘print bureaus’ – essentially, companies that get the CAD file and press ‘Print’,” concludes Salter. “While they serve a purpose, there is no effective engineering support and little regard for the application, only production.

“For high-risk sectors where part suitability and quality are paramount, so much more is required – that is why we created the DMC. From advanced alloys and polymers to silicone, we use state-of-the-art AM equipment and leverage our team’s expertise to help customers fully exploit the incredible possibilities of AM and provide them with end-use ready parts.”

With a greater focus on the UK space sector than ever before, the fact that new AM businesses like the DMC are being launched amid a global pandemic and post-Brexit is extremely encouraging. It highlights momentum within the advanced manufacturing supply chain and the arrival of accessible, high-quality digital production to UK shores.

“This is an incredibly exciting time for the UK space industry,” Curtis-Rouse concludes. “We have far greater access to leading production technologies than ever before. I have seen, first-hand, how this directly enables British space innovators. The UK space industry and its emerging supply chain must be adequately equipped and supported to proactively innovate, keeping pace with the global market and ensuring that the UK is a global leader and proud space-faring nation.”

With the UK Government’s target effectively eight years away, momentum is building. While funding innovation and research is critical, it will mean little without ensuring there is a well-established local supply chain to meet the growing industry’s highly-specialised requirements. If the UK is to compete at a global scale, new manufacturing processes like AM could be key. Not only can it cut weight and allow novel part designs, but it can reduce time-to-market and accelerate development. Better still, AM is enabling the creation of spares in orbit and, potentially, the construction of lunar and Mars bases – ideas once dismissed as science fiction are becoming reality and faster than you might expect.